Network of Controlling Values

For this semester of How Writers Read, I chose to read Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children. Initially, this book excited my “reading for,” as a strange, fantastical piece of fiction that had just been adapted for a film directed by Tim Burton. I am always drawn to fantasy, especially gothic fantasy, although I am skeptical of the “Hero’s Journey” format, as it is so popular. I was pleased, then, by Riggs’ frequent use of pictures in the book. The multi-media usage added a dimension to the book that created more of an experience than I was used to. As I read, the pictures worked to support the text where it might have confused me, just as the many mysterious letters, pictures, and tidbits of information in the story helped Jacob piece together the truth of his grandfather’s life and his sense of his own identity.

Upon starting to read the novel, we take a foggy and gloomy trip to Cairnholm, Wales – the setting of Abraham Portman’s thrilling monster stories. As a child, his grandson Jacob clung to his every adventurous word, following grand tales of levitating children and an enchanted children’s home that Abraham held as truth. At age fifteen, Jacob leaves his job one afternoon after receiving a frantic phone call from Abraham, defenseless against the monsters he is convinced are coming for him. By the time Jacob makes it to the empty home in sunny Circle Village, his grandfather is lying maimed in the forest behind his home. Jacob sees a hideous monster scuttling around in the dark as he clutches Abraham, who is just alive enough to deliver his last words:

“‘Find the bird. In the loop. On the other side of the old man’s grave. September third, 1940… Emerson – the letter. Tell them what happened, Yakob.’” (Riggs, 37).

The novel has an interesting emphasis on the contrast between what Jacob calls “Before” and “After” – two distinct phases of his life that are separated irrevocably by his discovery of the truth.The first half of the book features an apathetic, lost Jacob, reeling from the death of his grandfather and searching endlessly for something he feels is lacking in his life. His curiosity and desire to explore was suppressed at a young age by his parents, who envisioned more practical ambitions for him: “…so one day my mother sat me down and explained that I couldn’t become an explorer because everything in the world had already been discovered. I’d been born in the wrong century, and I felt cheated” (Riggs 13)

As soon as he enters the time loop in Cairnholm, however, he experiences a utopian parallel of the world he left behind: a safe, sunny day in 1940 that constantly repeats, doesn’t age any of its inhabitants, and seems to hold the answers to his loosely constructed identity among the minds and secrets of the Peculiars.

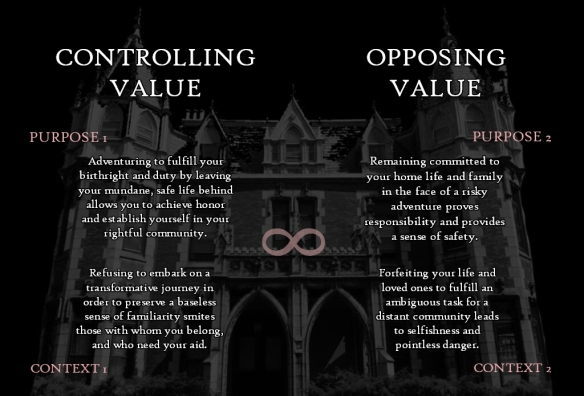

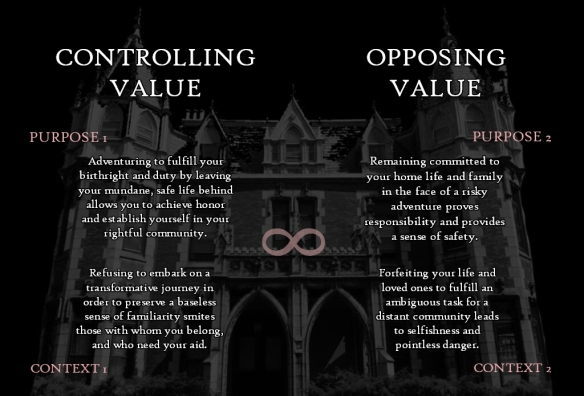

As Jacob transfers into and out of the loop, he is presented with an antimony between his existence within the present and peculiar worlds. Miss Peregrine, the headmistress of the school, is weary of his travel back into the normal, or “coerfolc,” world, fearful for his safety and secrecy; however, Jacob travels through the novel yearning for a piece of information – a key to his past, abilities, or identity – that is life-altering enough to make him stay. Thus, we are presented with the basis for Jacob’s network of controlling values, an idea founded in Robert McKee’s theory of controlling ideas and counter ideas. According to McKee, a controlling idea “expresses the core meaning of the story” by examining the positive or negative value and cause of this particular idea (McKee 115). With its complementary Opposing Value, this is the conflict between Jacob’s desire to find the truth, the hollows, and himself; and the safety of remaining in his mediocre, albeit safe, normal life. With the help of my reading group members and leader, I worked out the following network.

Jacob feels tied to his ordinary life by a sense of familiarity and comfort. As he begins his adventures to the time loop, he expresses, “I wanted, in that moment, for everything to go back to the way it had been before we came here; before I ever found that letter from Miss Peregrine…” (Riggs 268). However, this is a yearning for safety from danger over any extraordinary value of life: his parents are often too drunk or too involved in their own occupations and lives to give Jacob a loving, considerate place in their world, and he feels out of place. His grandfather’s death, as well as the clues he leaves behind, incites questions for Jacob that cannot be answered in his life outside the loop. His discovery that he is peculiar actually comes as a relief to him, and moves him tremendously: “I’d always known I was strange. I never dreamed I was peculiar. But I could see things almost no one else could… I wasn’t crazy or seeing things or having a stress reaction…” (Riggs 247). Jacob is the “chosen one” – after Abraham’s death, he the only known peculiar to be able to see the hollows: the monstrous, soulless beasts that killed his grandfather. This is the key to his identity, his true self, that begins to anchor him in the time loop. In addition to the imminence of the peculiar apocalypse, Jacob ultimately solidifies his controlling value as winner. In this choice, not only does he join his true community and duty, but he begins to conquer his fear of the dangerous unknown – which, to Jacob, is not nearly as “unknown” as his fellow peculiars, blind to the ravaging monsters that only he can see. The book ends with him actively choosing to embrace the After, even in the face of bombs, violence, and danger in the distance, indicating that in allowing his controlling value to win out, Jacob finally knows what he is fighting for: the safety of his new community, but perhaps more importantly, himself.

Form and Genre

In her blog that works with this method, Jenna examined how the novel defies its YA/children’s genre conventions. As we read and travel further into Jacob’s journey, the language and vocabulary become a lot more serious and probably difficult for a child to understand, but the novel can still be considered young adult fiction. It’s centered on a teenager who runs away from home to find himself, and ends up entering a love triangle; however, this is where the plot begins to break the conventions of the YA genre. According to Jane Gallop, this is common, as “…rare is the text which completely follows the rules of a genre: even the most conventional will usually display some individual expressivity, some originality in its details” (Gallop 10-11).There are elements of many different kinds of fiction that further specialize the book, like adventure, coming of age, fantasy, and a “through the wardrobe,” time-and-space-portal temptation. Furthermore, Jacob enters a mildly disturbing love triangle with his own deceased grandfather and the object of their affection, Emma, who hasn’t aged in 80 years. Jacob wins…by default, which is pretty sad, but it still stands. He wins the girl, finds himself, and gets to lead a brigade of loyal peculiar children into battle against hideous monsters.

In his essay “Counter-Statement,” Kenneth Burke describes five different forms that can indicate how pieces of a narrative interact with each other as they progress. One aspect of form he describes is the syllogistic progressive form, which “is the form of a mystery story, where everything falls together, as in a story of ratiocination by Poe” (Burke 124). According to Burke, in a story that follows the syllogistic progressive form, “the arrows of our desires are turned in a certain direction, and the plot follows the direction of the arrows” (124). In Miss Peregrine’s, one of the most important motifs to the plot is the collection of Abraham’s final words. The inclusion of each of these clues quite neatly sets our expectations for the rest of the book, as we reasonably assume the questions that these cryptic words incite will be answered. Sure enough, the satisfaction of each of these unanswered clues act as stepping stones for Jacob on his path to discovering the truth: he finds Abe’s letter from a Miss Peregrine in a Ralph Waldo Emerson book; finds the time loop set perpetually on September 3rd, 1940 with Miss Peregrine, who can shapeshift into a bird; past the “grave,” or museum display, of the Old Man, a 2700-year-old corpse preserved in the bog of Cairnholm. The progressive explanation of each clue works to steadily pace Jacob’s journey, as well as the narrative itself.

Burke also claims that peripety, or the “reversal of the situation,” is an effective result of the syllogistic progressive form in that it reverses the readers’ expectations. At the end of the book, when Miss Peregrine seems unable to shift back into her human form and the time loop cannot be reset, our motif fizzles from existence as the nightly bomb show actually wrecks the mansion. For the first time in nearly 80 years for the children of the loop, tomorrow will be September 4th, 1940, which indicates a few different dynamics within the text. As it subverts the syllogistic progressive form by altering the object of repetition, this change in day signifies a complete and irrevocable change in the lives of the characters, with no chance of return:

“…for the first time in a very long time, the days were moving again. Some of them claimed they could feel the difference; the air in their lungs was fuller, the race of blood through their veins faster. They felt more vital, more real” (Riggs 351).

Further, the nature of the change is one of forward motion, indicating the characters are moving on into a new realm and adventure. Although there are sequels, the ending of this book is self-contained and satisfying on its own, because the change of something as heavily important as the day with regard to the time loop (and consequently, the so-far consistent pattern of syllogistic progressive form) is so irreversible that there is at once a sense of closure and clarity, despite the new journey ahead.

However, at the climax of the novel, we are introduced to multiple instances of the repetitive form that have been operating unconsciously in Jacob’s life. According to Burke, the repetitive form is “the consistent maintaining of a principle under new guises” (125). In Jacob’s case, the “principle” is a wight – a hollow that has consumed enough souls to regain a semblance of a human form. They can take many different shapes, which makes them so dangerous; this particular wight’s most recent disguise was a mysterious birdwatcher that arrived on the island just after Jacob. He reveals himself to Jacob, Emma, and a few other peculiar children, but targets Jacob as he perfectly recreates the voice of Jacob’s middle-school bus driver, the family landscaper from his childhood, and none other than Dr. Golan, the psychiatrist Jacob confided in after his grandfather’s murder. It was this Dr. Golan that originally convinced both Jacob and his parents to travel to Cairnholm, now clearly to trap and kill the young peculiar. This wight has been following Jacob throughout his life, disguising himself under different forms without Jacob realizing; however, he has been substratally guiding Jacob closer to his identity – his unique peculiar ability to see the hollows – than any of his family members or his fellow peculiars ever have. Jacob simply could not see him before now, which is, quite literally, the key to the gift that distinguishes him from others in the peculiar world.

Codes

Jacob’s journey to find and understand the world in which he belongs is tedious, and finding the loop is only the beginning. Silverman, along with the help of Barthes, discusses five “codes” that work in a text to widen our rhetorical perspective and discussion of the text. According to Silverman, “The codes enumerated by Barthes would seem capable of invading the classic text on multiple levels, ranging from individual signifiers to larger syntactic and narrative constructions” (250). Essentially, examining codes in a particular text helps us understand how the dimensions of each code interact and intersect around one central conflict, and that point of conflict is where we as an audience make space to understand the rhetoric of the one overarching “cultural code.”

One of the codes that Silverman outlines is the hermeneutic code, which “inscribes the desire for closure and truth. However, this code provides not only the agency whereby a mystery is first suggested and later resolved, but a number of mechanisms for delaying our access to the desired information” (257). Silverman discusses ten “morphemes,” or parts of the code, which can vary in order and don’t all need to be present in a narrative to analyze its hermeneutic code. Miss Peregrine’s Home includes nearly all ten, but I will focus on six that are most relevant to the text.

The thematization morpheme, which involves “the emphasizing of the object which be the object of the enigma” (258), is the first of the ten described in his essay, but actually does not come into play for us until Jacob arrives at Cairnholm. Before that, there is a proposal that an enigma exists, when Jacob’s wholly uninteresting life is interrupted by the murder of his grandfather, and we hear those haunting last words:

“‘Find the bird. In the loop. On the other side of the old man’s grave. September third, 1940… Emerson – the letter. Tell them what happened, Yakob.’” (Riggs, 37).

After this, Jacob’s life becomes changed forever – on the other side of the proposal of the enigma is Jacob’s After. Throughout the beginning stages of his After, we are provided with multiple instances of formulation – supplementations to the mystery that emphasize it. This is where the steps of the previously mentioned syllogistic progressive form come in, as they work to confirm the mystery by satisfying each of the clues laid out in Abe’s final words, but don’t quite lead us to the ultimate answer. The first of these is actually the last of the clues Abe gave to his grandson; Jacob’s Aunt Susie found a Ralph Waldo Emerson book with Jacob’s name on it, and so she gave it to him. However, there was more than simply a book: “…something slipped out from between the pages and fell to the floor. I bent to pick it up. It was a letter. Emerson. The letter. I felt the blood drain from my face.” Each of the consequent supplementations involves a similar bone-chilling reaction from Jacob, confirming that these are the steps to amplify the mystery he is trying to solve.

When the continued supplementations bring our protagonist to the island of Cairnholm, we see the thematization that, to me, made Jacob’s mediocre life Before seem nearly out of place (conducive to Jacob’s feelings within the Before). Cairnholm is gloomy, rocky, and incredibly hard to get to. Jacob’s first impression is meaningful in this regard, as he observes,

“It was my grandfather’s island. Looming and bleak, folded in mist, guarded by a million screeching birds, it looked like some ancient fortress constructed by giants. As I gazed up at its sheer cliffs, tops disappearing in a reef of ghostly clouds, the idea that this was a magical place didn’t seem so ridiculous” (Riggs 70).

The request for an answer morpheme, which “facilitates narrative movement” (260), seems self-explanatory, but Jacob’s initial request is not explicit. When he finds the time loop and is brought to Miss Peregrine, his ignorance regarding the world of peculiars is a request enough. Miss Peregrine, surprised at his lack of information, commands him:

“‘Sit,’ so I squeezed into [the chair]. She took her place at the front of the room and faced me. ‘Allow me to give you a brief primer. I think you’ll find the answers to most of your questions contained herein’” (Riggs 153).

The suspended answers, partial answers, and jamming morphemes invade the text heavily on Jacob’s journey in the loop. Miss Peregrine and the peculiar children seem always to be hiding something from him, and that “something” is generally held to be the answer that Jacob needs for his mission. Emma herself risks punishment by telling Jacob that he’s peculiar – a transformative piece of information that makes up the very core of his identity. On a few occasions, upon instances of jamming, Jacob expresses this frustration in a matter of revealing how upset he is by the suspension of answers; it is often in these moments that he is treated to some sort of partial disclosure. For instance, after Emma confides in Jacob what happened between her and Abraham, he asks about Victor, a peculiar boy who resides, dead, in one of Miss Peregrine’s bedrooms.

“I can’t,” she said.

“That’s all I’ve been hearing! I can’t talk about the future. You can’t talk about the past. Miss Peregrine has us all tied up in knots. My grandfather’s last wish was for me to come here and find out the truth. Doesn’t that mean anything?” (Riggs 235).

The source of this withholding comes either directly from or per the request of Miss Peregrine. In this way, she is a manifestation of the suspended and partial answers morphemes. Miss Peregrine is incredibly restrictive with the information revealed to Jacob, either through the peculiar children or through her own doing. She will often gradually disclose the details Jacob desires, only to leave out the rest of the story that she has deemed unfavorable to impart. For example, Miss Peregrine hesitantly explains to Jacob that the children would die if they left their loop for the present, as “all the many years from which they have abstained will descend upon them at once, in a matter of hours” (Riggs 210-211). Jacob then proposes the idea that they could leave the island from 1940 if they pleased, though Miss Peregrine vaguely suggests staying in their loop is the best option considering “other dangers”.

“What other dangers?”

“Nothing you need concern yourself with. Not yet, at least” (Riggs 213).

The disclosure morpheme in the case of this novel is complicated, in that it may seem mimetically to result from the culmination of the other morphemes, but in fact does not. At the climax of the novel, when Jacob, Emma, and a few other peculiar children come face-to-face with the wight, they are put up against a hollow. To the other peculiar children, this hollow can only be distinguished by its shadow on the ground; however, Jacob is reacquainted with the very same hideous, soulless creature that killed his grandfather and haunted his nightmares.

“I saw it, lurking among the troughs. My nightmare. It stooped there, hairless and naked, mottled-gray-black skin hanging off its frame in loose folds, its eyes collared in dripping putrefaction, legs bowed and feet clubbed and hands gnarled into useless claws…” (Riggs 298)

This graphic, repulsive description of the hollow is the first time we are explicitly treated to any full description of the enemy the entire book. The people in Jacob’s life until this point have tried to suppress or regulate his curiosity, knowledge, and very identity: his parents tried to convince him it was a rabid dog that killed his grandfather, and Miss Peregrine very strictly kept him from any piece of truth that she did not give him herself. Some pieces of the puzzle leaked through, due to Emma’s love for him and him threatening some of the other children for information, but the hollow reveals itself to Jacob fully, immediately, in all of its abhorrent truth. The children’s encounter with the hollow is not the disclosure morpheme resulting from the set of heremeneutemes we have been tracking throughout the book; the hollow skipped every morpheme, created no sense of mystery or repression, and revealed itself to the only person who could see it in its own single instance of disclosure, consequently revealing to Jacob his identity and the difficult answer he has been hunting so desperately.

This points to several instances of the symbolic code invading the text. According to Burke, the symbolic code is “the articulation of binary oppositions, with the setting of certain elements ‘ritually face-to-face like two armed warriors.’ These oppositions are represented as eternal and ‘expiable’” (270). The novel begins by explicitly establishing the “antithesis” between Before and After as a transformative change in Jacob’s life that cannot be undone or reconciled. This antithesis invades the text in a few different ways, even ones that Jacob himself does not realize. Obviously, the Before/After antithesis with regard to his discovery of the loop points to an antithesis between staying/leaving, and even further between the normal world/the peculiar world, which Jacob decidedly cannot straddle. He must choose between the worlds, but before this climactic discovery of his identity and purpose, he did not have a good enough reason to stay. Out of this hollow encounter blossoms another Before/After antithesis: before and after he came face-to-face with the hollow, and consequently himself. Once again, the shift between these is irrevocable, and therefore solidifies Jacob’s place in the peculiar world and his need to say goodbye to his father.

A yet more complicated antithesis arrives from this latter Before/After dichotomy. From my examination of the hermeneutic code, there arises an antithesis between the peculiars/the hollows, but not in a sense of battle conflict – rather, in relation to Jacob’s identity. The ways each side went about revealing Jacob to himself were completely opposite, and puts Jacob in an isolated position in the middle of the conflict. This would suggest that Jacob’s unique peculiar ability prevents him from fitting in anywhere fully, whether it is an uninspired life with mediocre parents, a utopian time loop in Wales, or amongst the soulless damned that only he can see. On either extreme end of this antithesis lay Abraham, with his open revelation of his stories met with childlike wonder, and the hollows. To Jacob, in the end, these are the singular driving forces in relation to his identity: his ancestry and his ability. In a strange way, the two sides of this antithesis work together in their opposition, and Jacob finds himself within the central conflict in a very unique role. Although it may not be completely amongst any homogenous community, it is where he is meant to be; the solace in knowing that, keeping both Abe and the hollows in mind, is what drives him forward to embark on his great adventurous mission.

Narrator/Addressee

Throughout the book, Jacob is endlessly motivated by his remembrance of his grandfather, as well as the shame and guilt he feels about not taking Abe’s stories seriously in life. His mission, centered around finding the truth about his grandfather and also himself, is therefore narrated to Abe. However, according to the work of Seitz, this initial rejection of Abe’s tales were necessary for Jacob to later write his own journey through the world of the peculiars. With the help of Bloom, Seitz argues that “strong reading…must reject the implied reading in favor of a virtual reading, a misreading, that comes to be written. Bloom’s study is that of the ‘relationships between texts,’ how texts misread their predecessors in order to create space for their own writing” (150). After getting bullied in school at a young age for his belief in his grandfather’s adventure stories, Jacob decides to reject the stories for his own social well being: “I told him that a made-up story and a fairy tale were the same thing, and that fairy tales were for pants-wetting babies, and that I knew his photos and stories were fakes” (Riggs 20). At age fifteen, when Abe is killed and Jacob is left to find the truth on his own, he does not have the extended knowledge of the peculiar world that he would have had if he had continued to submit to Abraham’s truth. This “space,” therefore, is more like a lacking blank, which Jacob must make up for by setting out to “write” his own journey. All he has are his grandfather’s last words and the pictures he left behind – he must supplement the information about his story by asking (or threatening) his fellow peculiars and finally facing a hollow, who tells him everything he needs to know.

Just as Jacob narrates to Abe throughout his journey, Abraham narrates back to Jacob, as well as his father. Jacob and Mr. Portman take two different ethical approaches to “reading” Abraham’s stories, which Seitz explains: “A rhetoric of reading, in other words, includes the reader’s ethos, which we might begin to locate along a continuum of submission and resistance.” Where Jacob’s role in regard to Abe’s stories and mission is one of submission – that is, curiosity and willingness to adventure, assuming there is truth to Abe’s words – Mr. Portman’s role is one of reluctance, disgust, and defeat. Mr. Portman’s relationship with his father was one of distance, and he describes Abe as “an emotional Fort Knox.” He recognizes Jacob’s closeness to Abe almost bitterly, as he tells his son: “‘It took him fifty years to get over his fear of having a family. You came along at just the right time’” (Riggs 101).

Mr. Portman’s jealousy of Abe and Jacob’s relationship, which manifests in an accusation that Jacob “worshipped” him, indicates that he is not as resistant to his father’s stories and relationship as he might think. Indeed, Seitz tells us, “Of course, ‘submission’ and ‘resistance’ are metaphors for ways of reading, and it would be wrong to suggest that the reader ever stands entirely on one side or the other” (151). Mr Portman’s relationship with his father was doomed irrevocably since childhood, but his jealousy of Jacob suggests his repressed submission to Abraham, whether it was his stories or his emotional capacity for familial bonds; thus, he feels inadequate in the face of Jacob’s reverent relationship with Abe.

Jacob also confirms the suggestion that no reader can ever be on either end of Seitz’s continuum, given his resistance throughout his adolescence. An argument can be made that Jacob is more willing to revisit and once again submit to Abraham’s stories because he is peculiar, where Mr. Portman is not, and thus Abraham focused his narration on Jacob. Jacob is predisposed to his submission because Abe knows he is peculiar, and thus he is the one who is delivered Abe’s last words, which entreats Jacob on a mission Abe knows only he can fulfill. However, despite Mr. Portman’s un-peculiarity, he was presented time and again with opportunities to believe his father and take up arms to help him against the hollows that hunted him. Instead, he wrote Abe off as a demented, paranoid fool and did not even remotely entertain the idea of believing him. This leaves Jacob the space to submit to whatever of Abe he has left and create his own story, venturing off to finish what his grandfather started.

Final Reflection

When I entered How Writers Read this semester, I was actually slightly nervous. I had heard from my friends who had taken the class that it required a completely different set of skills, information, and learning. They were right, but I surprised myself with how much the course material fascinated me. “Getting” the readings and methods in the beginning was very difficult for me, and even though I desired to get a stronger grasp on the methods, I felt like I was hitting brick walls at every corner. The first blog method that I finally got was the blog I wrote for The Bluest Eye – the first time I feel like I thoroughly applied Writing Arts Core Value Two. The book lent itself conducively to the examination of symbolic codes, but I also felt like I had more or less of a breakthrough, and sort of ran with it. I learned the value of putting myself through “sitting with” texts and methods that were difficult to understand initially and that frustrated me, to be rewarded with a bit of a learning curve and context to begin understanding the rest of the material. In my own relationship with the course, however, I don’t feel like I am finished yet, and so I’m thrilled to be taking it again as a reading group leader next fall!

My demonstration of understanding and applying Core Values One and Three can be seen in the variation in books that our reading group chose. They varied heavily in genre, from fantasy fiction, to mystery-drama, to social-commentative fiction, to dystopian. Similarly, the variety in the texts we read for the methods points to my ability to read critically and apply these lessons in my blog posts. The method readings ranged in experience, mainly in accessibility of language (i.e. Gallop was easily understandable and a godsend, where reading Seitz and Burke often felt like decoding Russian). My application of the methods improved over time, which can be seen in my work as well as in my confidence in completing the blogs. In relation to Core Value Three, the process of improving my understanding of the class readings meant challenging my prior perspective on reading and writing, which I found to be too narrow. I needed to get used to thinking and operating with a different, more inclusive and specialized vocabulary: learning was now “distinguishing,” and something like surface-level or realistic was now “mimetic,” to give some examples. I also needed to wrap my head around the idea that the dimensions of a text can expand spatially, and not just theoretically – that sets of controlling values and symbolic codes can expand out from a central point of conflict in any directions. Drew drew a diagram (ha) in our meeting that helped me understand how to make a space for all of the codes and forms to come together. As a visual learner, I know have a deeper understanding of this for application in the texts I read.

Overall, I thoroughly enjoyed the work that I did in this course, and I have a greater understanding of rhetoric and how it interacts with a text, or how it helps us examine aspects of a text that interact with each other, or how it helps us comprehend how we ourselves interact with a text. However, I think my friends need a break from hearing out my codes and interpellations (and refraining from telling me to shut up) so I’ll check back in next fall when I dive back in again!

decide to leave their baby at home during a dinner party next door, checking on her every half hour. The baby, Cora, gets mysteriously kidnapped while they are next door. The novel focuses on finding and getting this baby back home safely, during which secrets between the young couple are constantly being uncovered allowing for plenty of twists.

decide to leave their baby at home during a dinner party next door, checking on her every half hour. The baby, Cora, gets mysteriously kidnapped while they are next door. The novel focuses on finding and getting this baby back home safely, during which secrets between the young couple are constantly being uncovered allowing for plenty of twists.

her rocky mental state has been present since middle school? Would Anne have let Marco check on the baby if she knew what his plan was?

her rocky mental state has been present since middle school? Would Anne have let Marco check on the baby if she knew what his plan was?

After Detective Rasbach meets with Janice Foegle, we learn about Anne’s questionable and abusive past. Our view, along with the detective in the book’s view, of Anne changes. Rasbach no longer believes Anne to be innocent but he suspects Anne murdered Cora without remembering. He thinks Marco covered up his wife’s murder. Although probably common among such an intense and clueless mystery, us readers along with the detective, were annoyed with the constant change in theories about who committed the crime.

After Detective Rasbach meets with Janice Foegle, we learn about Anne’s questionable and abusive past. Our view, along with the detective in the book’s view, of Anne changes. Rasbach no longer believes Anne to be innocent but he suspects Anne murdered Cora without remembering. He thinks Marco covered up his wife’s murder. Although probably common among such an intense and clueless mystery, us readers along with the detective, were annoyed with the constant change in theories about who committed the crime.  past behavior of beating a girl up almost to death and her having no remembrance of it we question Anne, leading to the reader (actually along with Anne) convincing ourselves that Anne may actually have done it. That is until we get to Marco. When we find out about his money problems, kiss with Cynthia and relationship with “Bruce Neeland,” we question him, too. We question every character and situation that the writer wanted us to. Each character posed a challenge and embodies a mystery that needs to be solved. We followed the progression of the book along with the characters and we know that Anne and Marco were definitely The Couple Next Door.

past behavior of beating a girl up almost to death and her having no remembrance of it we question Anne, leading to the reader (actually along with Anne) convincing ourselves that Anne may actually have done it. That is until we get to Marco. When we find out about his money problems, kiss with Cynthia and relationship with “Bruce Neeland,” we question him, too. We question every character and situation that the writer wanted us to. Each character posed a challenge and embodies a mystery that needs to be solved. We followed the progression of the book along with the characters and we know that Anne and Marco were definitely The Couple Next Door.

world with a brand new gamut of truths to understand and uphold, what Rabinowitz would call a “narrative audience”; except, of course, when Detective Rasback claims he “knew it all along” numerous times throughout the investigation.”

world with a brand new gamut of truths to understand and uphold, what Rabinowitz would call a “narrative audience”; except, of course, when Detective Rasback claims he “knew it all along” numerous times throughout the investigation.”

In one word, reading this book is, well, devastating. The abuse and neglect are hard to read about, of course, but the feelings of isolation and inferiority are tangible. Generally, my “reading for” revolves around this concept of aesthetic emotion, but with this novel, I may have gotten more than I bargained for when I submitted to this text and allowed myself to be consumed by the mimesis. I think that one problem I find in my “reading for” is that I’m constantly grasping for ways to relate to the text. While I can grasp at the feelings of isolation and inferiority (Ummm hello, have you ever been a teenager?), I prepared myself before reading to be hyper-aware of the thematic elements of the text so I wouldn’t fall into my usual habit.

In one word, reading this book is, well, devastating. The abuse and neglect are hard to read about, of course, but the feelings of isolation and inferiority are tangible. Generally, my “reading for” revolves around this concept of aesthetic emotion, but with this novel, I may have gotten more than I bargained for when I submitted to this text and allowed myself to be consumed by the mimesis. I think that one problem I find in my “reading for” is that I’m constantly grasping for ways to relate to the text. While I can grasp at the feelings of isolation and inferiority (Ummm hello, have you ever been a teenager?), I prepared myself before reading to be hyper-aware of the thematic elements of the text so I wouldn’t fall into my usual habit.

This restatement of the theme continues throughout the novel, and until the very end of the scene, I discussed previously with Pecola believing she has blue eyes (a symbol of whiteness and beauty). While we know that Pecola doesn’t have this feature and she’s as “ugly” as ever, in reality, she believes she meets the standard of beauty finally and no longer has to suffer. Instead, she can be happy. To everyone else, though, Pecola is just insane.

This restatement of the theme continues throughout the novel, and until the very end of the scene, I discussed previously with Pecola believing she has blue eyes (a symbol of whiteness and beauty). While we know that Pecola doesn’t have this feature and she’s as “ugly” as ever, in reality, she believes she meets the standard of beauty finally and no longer has to suffer. Instead, she can be happy. To everyone else, though, Pecola is just insane.  Perhaps it stems from her parents. Both Polly and Cholly Breedlove suffered from their own traumatic experiences as young people are ashamed of their blackness, which, for them, represents ugliness. Claudia and Frieda aren’t as tragically fixated on these feelings of ugliness, though the dichotomy certainly operates within their own personal set of controlling values. Claudia, for example, reacts negatively and resents white girls for being deemed prettier are more valuable than her for nothing more than their whiteness. As best as she can, Claudia resists this dichotomy she’s been forced to exist within, as I mentioned before with her destruction and hatred of white baby dolls. Maureen operates on the opposite end of the spectrum. Racially, she is either mixed or black, but her skin color presents as extremely light, therefore she, too, is considered prettier than her black peers, and they resent her and are jealous of her simultaneously, just as if she were a white.

Perhaps it stems from her parents. Both Polly and Cholly Breedlove suffered from their own traumatic experiences as young people are ashamed of their blackness, which, for them, represents ugliness. Claudia and Frieda aren’t as tragically fixated on these feelings of ugliness, though the dichotomy certainly operates within their own personal set of controlling values. Claudia, for example, reacts negatively and resents white girls for being deemed prettier are more valuable than her for nothing more than their whiteness. As best as she can, Claudia resists this dichotomy she’s been forced to exist within, as I mentioned before with her destruction and hatred of white baby dolls. Maureen operates on the opposite end of the spectrum. Racially, she is either mixed or black, but her skin color presents as extremely light, therefore she, too, is considered prettier than her black peers, and they resent her and are jealous of her simultaneously, just as if she were a white.

Artym gets there? The whole story of Metro 2033 is leading up to this big discovery of the dark ones, and completion of Artyom’s main mission, to warn the others of what might be coming.

Artym gets there? The whole story of Metro 2033 is leading up to this big discovery of the dark ones, and completion of Artyom’s main mission, to warn the others of what might be coming.

They even had influence over Artyom in a psychological way, as he spoke of them as having “filled and warmed him” and “[gave] meaning to his existence” (Glukhovsky 458). If Artyom is the only being from the Metro with the ability to save them, it makes sense for them to do so revolving around Artyom. His story is also their story. If this is true, then

They even had influence over Artyom in a psychological way, as he spoke of them as having “filled and warmed him” and “[gave] meaning to his existence” (Glukhovsky 458). If Artyom is the only being from the Metro with the ability to save them, it makes sense for them to do so revolving around Artyom. His story is also their story. If this is true, then

I found it difficult to become this audience for Glukhovsky. Once I got past the sheer verboseness of the story, I found myself questioning or disliking most of the characters. It wasn’t until the last chapter of the novel (which, honestly, is when almost all of the story happens) until I made my move from only the actual audience, which I’ll always be, regardless of my reading for, to finding a place where I could slip into the role of authorial audience. It turned out that, through my questioning and dislike, I was on the right track all along.

I found it difficult to become this audience for Glukhovsky. Once I got past the sheer verboseness of the story, I found myself questioning or disliking most of the characters. It wasn’t until the last chapter of the novel (which, honestly, is when almost all of the story happens) until I made my move from only the actual audience, which I’ll always be, regardless of my reading for, to finding a place where I could slip into the role of authorial audience. It turned out that, through my questioning and dislike, I was on the right track all along.